It has often been said that war is the health of the State – but the argument could also be made that the reverse is more true: that the State is the health of war. In other words, that war – the greatest of all human evils – is impossible without the State.

The great Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises was once asked what the central defining characteristic of the free market was – i.e. since every economy is more or less a mixture of freedom and State compulsion, what institution truly separated a free market from a controlled economy – and he replied that it was the existence of a stock market. Through a stock market, entrepreneurs can achieve the externalization of risk, or the partial transfer of potential losses from themselves to investors. In the absence of this capacity, business growth is almost impossible.

In other words, when risk is reduced, demand increases. The stagnation of economies in the absence of a stock market is testament to the unwillingness of individuals to take on all the risks of an economic endeavour themselves, even if this were possible. When risk becomes sharable, new possibilities emerge that were not present before – the Industrial Revolution being perhaps the most dramatic example.

Sadly, one of those possibilities – in all its horror, corruption, brutality and genocide – is war. In this section, I will endeavour to show that, in its capacity to reduce the costs and risks of violence, the State is, in effect, the stock market of war.

All economists know the “fallacy of the broken window,” which is that the stimulation of demand caused by a vandal breaking a window does not add to economic growth, but rather subtracts from it, since the money spent replacing the window is deducted from other possible purchases. This is self-evident to all of us – we don’t try to increase our incomes by driving our cars off cliffs or burning down our houses. Although it might please car manufacturers and home builders, it neither pleases us, nor the people who would have had access to the new car and house if we did not need them for ourselves. Destruction always diverts resources and so bids up prices, which costs everyone.

(In fact, breaking a $100 window removes more than $100 from the economy, since all the time spent returning the window to its original state – calling the window repairman, deciding on the replacement, cleaning up the shards of glass, etc – is also subtracted from the economy as a whole.)

There will always be accidents, of course, and so repairs are a legitimate aspect of any free market. However, war can never be said to be an accident, is never part of the free market, and yet is commonly believed to be good for the economy – and must be, for at least some people, since it is pursued so often. How can these opposites be reconciled? How can destruction be economically advantageous, when it is so obviously bad for the economy as a whole?

We can imagine an unethical window repairman who smashes windows in order to raise demand for his business. This would certainly help his income – and yet we see that this course is almost never pursued in real life in the free market. Why not?

One obvious answer could be that business managers are afraid of going to jail – and that certainly is a risk, but not a very great one. Arsonists are notoriously hard to catch, for instance, and there are 61 |

so many hard-to-trace sabotages that can be undertaken. Poison can be added to the water supply that would incriminate a water supplier, which would take months to resolve – at which point the trail would be long cold. Foreign hackers could be paid to infiltrate competitor’s networks, or mount denial-of-service attacks on their web sites – sure doom for those who sell over the Internet.

Not convinced? Well, what about eBay? If you have a competitor who is taking away your business, why not just get a hundred of your closest friends to give him a bad rating, and watch his reputation – and business – dry up and blow away?

All of the above practices are very rare in the free market, for three main reasons. The first is that they are costly; the second is that they increase risks, and the third is the fear of retaliation.

THE COST OF DESTRUCTION

If you want to hire an arsonist to torch the factory of your competitor, you have to become an expert in underworld negotiations. You might pay an arsonist and watch him take off to Hawaii instead of setting the fire. You also face the risk that your arsonist will take your offer to your competitor and ask for more money to not set the fire – or, worse, return the favor and torch your factory! It will certainly cost money to start down the road of vandalism, and there is no guarantee that your investment will pay off in the way you want.

There are other tertiary costs to pursuing a path of “competition by destruction.” You can only target one competitor at a time, which is only partially helpful, since most businesses face many competitors simultaneously – some local, and some overseas and probably out of reach. Even if you are successful in destroying your competitor, you have opened a “hole” in the market, which will just invite others to come in – and perhaps compete even more fiercely with you. When it comes to competition, in most cases it is better to stay with “the devil you know.” It wouldn’t make much sense to knock out a small software competitor, for instance, and end up giving Microsoft a good reason to enter the market.

Also, if you are a business owner, competition is very good for you. Just as a sports team gets lazy and unskilled if it never plays a competent opponent, businesses without competition get unproductive, lazy and inefficient – a sure invitation to others to come in and compete. Successful businesses need competition to stay fit. Resistance breeds strength.

Also, what happens if you do manage to successfully sabotage your opponents? If you do it well, no one has any idea that you are behind the sudden spate of arson. What happens to your insurance costs? They go through the roof – if you can even get any! Furthermore, you will not be able to meet all the new demand right away, thus ensuring that clients will find alternatives, which will likely remain outside your control. Thus you have increased your costs, created incentives for potential customers to find alternatives and alarmed your employees – creating a dangerous situation where competitors are highly motivated to enter your field just when you are the most vulnerable to competition! Overall, not a very bright idea!

THE RISKS OF DESTRUCTION

Let us say you decide to pay a man named Stan to torch your competitor’s factory – well, the basic reality of the transaction is that Stan, as a professional arsonist, knows how to work the situation to his advantage far better than you do, since you are, ahem, new to the field. Stan knows that no matter what he does, you cannot go to the police for protection. What if he tapes your conversations and then blackmails you? Then your exercise in amoral competition suddenly becomes a lifelong nightmare of expense, guilt, fear and rage.

As mentioned above, what if Stan decides to go to your competitor and reveal your plans? Surely your competitor would pay good money for that information, since he could then go to the police and destroy you legally even more completely than you were hoping to destroy him illegally. A basic fact of criminal activity is that once the gloves come off, the results become very hard to predict indeed!

What if Stan goes to your competitor and says: “For $25,000, I was supposed to torch this place – for $30,000 I can just turn around and set quite a different fire!” This pendulum bidding war can turn into a desperately stressful money-loser for everyone concerned (except Stan, of course).

And who is to say that Stan is even a “legitimate” arsonist? What if he is an undercover agent of some kind? What if he has been sent by someone else in order to get some dirt on you? What if it turns out to be blackmail, or a set-up by your competitor? How would you know? Again – it is all very risky!

THE RISKS OF PERSONAL RETALIATION

Let us say that all of the above works out just the way you want it and Stan actually torches your competitor Bill’s factory – what might happen then? You have just created a bitter enemy who suspects foul play, knows that you have a good motive for torching his factory, and has nothing to lose. He might complain about you to the police, hire private investigators and put an ad in every local paper offering a cash reward of a million dollars for information leading to proof of your participation – so he can sue you and recover far more than a million dollars!

Either your new enemy will find out actionable information, and then go to the police, or he will find out unactionable information – hints, not proof – in which case he may choose to retaliate against you. Since you’ve been able to do it in a way that cannot be proven – and he now knows how – you have just educated a bitter and angry man on how to torch a factory and escape detection. Are you going to sleep safe in your bed? Are you sure that he’s going to target only your factory?

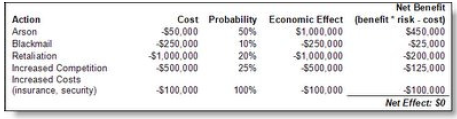

What does all this look like in terms of economic calculation? Have a look at a sample table below showing the costs and benefits of competition through arson. If we assign arson a cost of $50k, with a 50% probability of success, and a resulting economic benefit of $1m, we see a net benefit of $450k (50% of $1m – $50k in costs). So far so good. But if we include a 10% risk of blackmail, a 20% chance of retaliation, a 25% chance of increased competition – all reasonable numbers – and finally $100k in increased insurance and security costs – we can see that the economic benefits are erased very quickly (see below).

(Note that the above table only shows the economic calculations – these do not include the emotional factors of guilt, fear and worry, which are of great significance but hard to quantify. This is important because even if the above numbers were less disagreeable, the emotional barrier would still have to be overcome.)

As the above conservative example shows, it is not really worth it to attempt economic gain through the destruction of property – and that is exactly how it should be. We want people to be good, of course, but we also want strong economic incentives for virtue as well, to shore up the uncertain integrity of free will!

How does this relate to war and the State? Very closely, in fact – but with very opposite effects.

THE ECONOMICS OF WAR

The economics of war are, at bottom, very simple, and contain three major players: those who decide on war, those who profit from war, and those who pay for war. Those who decide on war are the politicians, those who profit from it are those who supply military materials or are paid for military skills, and those who pay for war are the taxpayers. (The first and second groups, of course, overlap.)

In other words, a corporation which profits from supplying arms to the military is paid through a predation on citizens through State taxation – and under no other circumstances could the transaction exist, since the risks associated with destruction outlined above are equal to or greater than any profits that could be made.

Certainly if those who decided on war also paid for it, there would be no such thing as war, since war follows the same economic incentives and costs outlined above.

However, those who decide on war do not pay for it – that unpleasant task is relegated to the taxpayers (both current, in the form of direct taxes and inflation, and future, in the form of national debts).

Let us see how the above analysis of the costs of destruction changes when the State enters the equation.

THE COSTS OF MILITARY DESTRUCTION

If you want to start a war, you need a very expensive military – which must also be trained and maintained when there is no war. There is simply no way to recover the costs of that military by invading another country – otherwise, the free market would directly fund armies and invasions, which it never does. Or, if you would prefer another way of looking at it, you can only invade another country by destroying large portions of it, killing many of its citizens, and then fighting endless insurgencies. Given the costs of invasions and occupations – always in the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars – what profits could conceivably be extracted from the bombed-out country you are occupying? That would be like asking a thief to make money by fire-bombing a house he wanted to steal from, and then staying and keeping the occupants hostage. Madness!

Thieves don’t operate that way – and neither would war, without the presence of the State and the money of the taxpayers.

Since the taxpayer’s money pays for the war, the costs of destruction for those who start the war are very low – how much does George Bush personally pay for the Iraq invasion? While it is true that those who profit from the war also pay the taxes needed to support the war effort, the amount they pay in taxes is far less than they receive in profits – again, facts we know because there are always people willing and eager to supply the military.

THE RISKS OF ANNIHILATION

Those who decide on war and those who profit from war only start wars when there is no real risk of personal destruction. This is a simple historical fact, which can be gleaned from the reality that no nuclear power has ever declared war on another nuclear power. The US gave the USSR money and wheat, and yet invaded Grenada, Haiti and Iraq. (In fact, one of the central reasons it was possible to know in advance that Iraq had no weapons of mass destruction capable of hitting the US was that US leaders were willing to invade it.)

Avoiding the risk of destruction was the reason that the USSR and the US (to take two obvious examples) fought “proxy wars” in out-of-the-way places like Afghanistan, Vietnam and Korea. As we shall see below, the fact that the risk of destruction is shifted to taxpayers (and taxpayer-funded soldiers) considerably changes the economic equation.

THE RISKS OF MILITARY RETALIATION

The “risk of retaliation” in economic calculations regarding war should not be taken as a general risk, but rather a specific one – i.e. specific to those who either decide on war or profit from it. For example, Roosevelt knew that blockading Japan in the early 1940s carried a grave risk of retaliation – but only against distant and unknown US personnel in the Pacific, not against his friends and family in Washington. (In fact, the blockading was specifically escalated with the aim of provoking retaliation, in order to bring the US into WWII.)

If other people are exposed to the risk of retaliation, the risk becomes a moot point from an amoral economic standpoint. If I smoke, but some unknown stranger might get lung cancer, my decision to continue smoking will certainly be affected!

EXTERNALIZING MILITARY RISK

The power of the State to so fundamentally shift the costs and benefits of violence is one of the most central facts of warfare – and the core reason for its continued existence. As we can see from the above table regarding arson, if the person who decides to profit through destruction faces the consequences himself, he has almost no economic incentive to do so. However, if he can shift the risks and losses to others – but retain the benefit himself – the economic landscape changes completely! Sadly, it then it becomes profitable, say, to tax citizens to pay for 800 US military bases around the world, as long as strangers in New York bear the brunt of the inevitable retaliation. It also becomes profitable to send uneducated youngsters to Iraq to bear the brunt of the insurgency.

EXTERNALIZING EMOTIONAL DISCOMFORT

The fact that the State shifts the burden of risk and payment to the taxpayers and soldiers is very important in emotional terms. If the “arson” example could be tweaked to provide a profit – say, by reducing the risks of blackmail or retaliation – the other risks would still accrue to the man contemplating such violence. Such risks would cause emotional discomfort in all but the most rare and sociopathic personalities – and the generation of negative stimuli such as fear, guilt and worry would still require more profit than the model can reasonably generate.

Thus the fact that the State externalizes almost all the risks and costs of destruction is a further positive motivation to those who would use the power of State violence for their own ends. Once you throw in endless pro-war propaganda (also called “war-nography”), the emotional benefits of starting and leading wars funded by others can become a definitive positive – which ensures that wars will continue until the State collapses, or the world dies.

IN OTHER WORDS, THE STATE IS WAR

If the above is understood, then the hostility of anarchists towards the State should now be at least a little clearer. In the anarchist view, the State is a fundamental moral evil not only because it uses violence to achieve its ends, but also because it is the only social agency capable of making war economically advantageous to those with the power to declare it and profit from it. In other words, it is only through the governmental power of taxation that war can be subsidized to the point where it becomes profitable to certain sections of society. Destruction can only ever be profitable because the costs and risks of violence are shifted to the taxpayers, while the benefits accrue to the few who directly control or influence the State.

This violent distortion of costs, incentives and rewards cannot be controlled or alleviated, since an artificial imbalance of economic incentives will always self-perpetuate and escalate (at least, until the inevitable bankruptcy of the public purse). Or, to put it another way, as long as the State exists, we shall always live with the terror of war. To oppose war is to oppose the State. They can neither be examined in isolation nor opposed separately, since – much more than metaphorically – the State and war are two sides of the same bloody coin.